Electrostatics of charged macromolecules

Seminar about electrostatics of charged macromolecules, written for presentation in 1st year of my master's studies, with help from my advisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Matej Kanduč

Abstract

Electrostatic interactions between charged macromolecules in water solutions are mediated by ions. In general, this is an intractable many-body problem, but the analysis is simplified by considering two extremal regimes. Central to this is the coupling parameter \(\Xi\), a dimensionless quantity that characterizes two distinct physical regimes. For low values of \(\Xi\), we talk about the weak-coupling regime, where a mean-field description using the Poisson-Boltzmann equation is appropriate. The weak-coupling limit predicts purely repulsive forces for like-charged macromolecules, contradicting simulation and experimental results. This apparent contradiction is resolved at high values of \(\Xi\), where counterions are highly correlated, resulting in net attraction between like-charged surfaces. This explains the phase-coexistence experimentally observed in systems of membranes and gives a sound theoretical explanation for similar phenomena such as DNA condensation. This seminar presents the key results of the weak/strong coupling dichotomy, supported by experimental and simulation examples from the relevant literature.

Introduction

Electric charges and electrostatic interactions are abundant in soft matter and biological systems. Soft matter is typically composed of large molecules, so-called macromolecules, with examples like colloids, DNA, lipid membranes and industrially significant charged polyelectrolytes [1].

The length scale of these macromolecules is mesoscopic, with macromolecules composed of a large number of atom-sized constituents, but still much smaller than the macroscopic scale of some appreciable quantity of such material.

Oftentimes these macromolecules have highly charged surfaces, acquired when a substance is dissolved in water. This can happen by the dissociation of surface groups or by the adsorption or binding of ions from solution onto a surface [2].

Attractions and repulsions between these surface charges, strong enough not to be overpowered by thermal fluctuations, constitute prominent factors determining the behaviour and properties of soft matter. The water solution of macromolecules also contains oppositely charged ions, so-called counterions, which compensate for the macromolecule surface charges when looking at the solution as a whole, i.e. an electroneutrality condition is imposed. The counterions form clouds around the charged macromolecules and tend to screen their bare charges. As we will see, the shape and dimension of these clouds will be crucial to understanding the emerging interactions between macromolecules in such a solution.

In general, the dynamic of such a system is a complicated many-body problem. As we know from the famous example of the three-body problem, such many-body problems don’t have closed-form solutions. While the equations describing such a system are possible to write down, the emerging phenomenology is rich and as we will see, at places even surprising.

The study of charged macromolecule interactions began with Gouy [3] and Chapman [4], who first formulated the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. The modern systematic treatment starts with Edwards and Lenard [5], which formulated the many-body problem as a field theory. Podgornik and Žekš [6] showed that the Poisson-Boltzmann equation arises as a saddle-point approximation of this field theory, the approximation being valid in the so-called weak-coupling regime, valid for monovalent ions and small charge densities. Netz [7] rounded out this dichotomy by deriving a theory which becomes accurate in the opposite strong-coupling limit. Since then, much more work on the subject has been done, culminating in review articles such as Ref. [2].

Problem statement

Before proceeding with the model in concrete geometry, we take note of some starting simplifying assumptions of our model. This crude model is still far from trivial and offers a coherent understanding of electrostatic effects. We assume that counterions are charged point particles, i.e. they interact with other counterions only via the Coulomb interaction. They interact with the macromolecules via the Coulomb interaction and are also able to transfer momentum and exert pressure on their surface.

We also assume a coarse-grained description of the solvent water molecules. The collective action of water molecule dipoles is taken into account by the continuum description, by modifying the Coulomb interactions between charged particles by the relative dielectric constant \(\varepsilon\). Its value at room temperature is \(\varepsilon \sim 80\) [9].

The last assumption is the so-called counterion-only approximation. Real solutions often contain salt ions, which are themselves composed of both counterions and coions. This mixture of ions of opposite charge will give rise to screening. This modifies the electrostatic interactions with an exponential falloff. To avoid this, we will assume that our solution only contains charged macromolecules and oppositely charged counterions. For each surface charge, there is an oppositely charged counterion present in the solution. This is a valid approximation at low salt concentrations when the screening length is much larger than other scales in our system.

Single-plate geometry

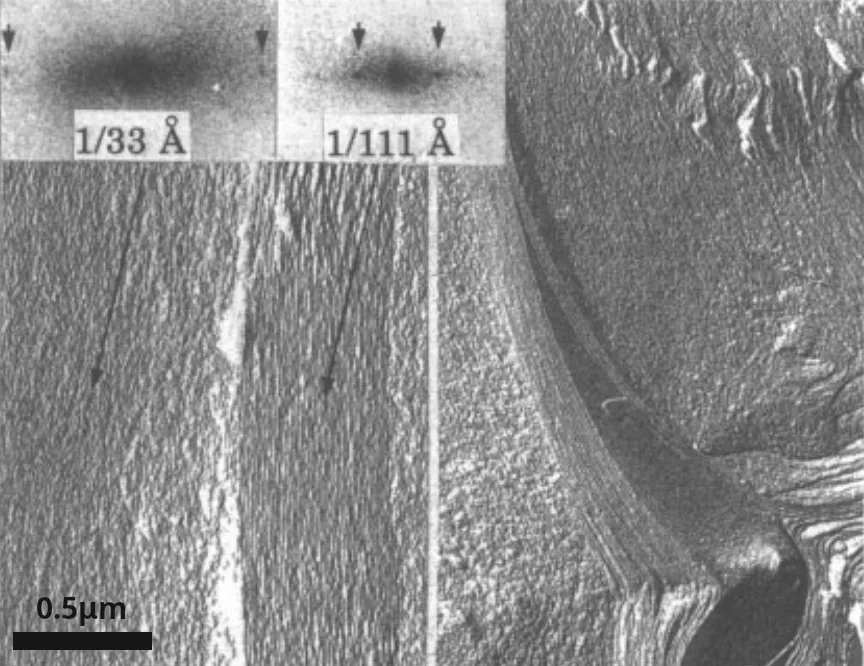

Geometry of the macromolecules is another assumption facilitating a tractable description. We will assume macromolecules to be charged planar surfaces. Such a planar geometry allows simple analysis and is also important as it can be readily realized in experimental setups that serve as confirmation to the theory (for an example, see Figure 1). While planar geometry is chosen for ease of analysis and experimental realization, it approximates physical reality well in many cases, as large macromolecules are locally flat at points of near-contact. Many key predictions from planar geometry are shared with other geometries, such as charged cylinders, flexible polymers and spheres.

We write down a Hamiltonian for a system depicted in Figure 2, with counterions of valence \(q\), located at positions \(\mathbf{r}_i\), close to an oppositely charged planar wall (see Figure 2) of charge density \(\sigma\), expressed in units of elementary charges \(e_0\) per unit area \begin{equation}H = \sum_i \sum_{j < i} \frac{q^2 e_0^2}{4\pi\varepsilon\varepsilon_0|\mathbf{r}_j - \mathbf{r}_i|} + \frac{q \sigma e_0^2}{2\varepsilon\varepsilon_0} \sum_i {z}_j, \label{eq:hamiltionian-raw}\end{equation} where the first term is the sum of all counterion-counterion interactions and the second term is the wall-counterion interaction.

To get insight into the basic behavior of the system, we will now consider some scales characterizing our electrostatic interactions. The first of these is the distance at which two unit charges interact with the thermal energy \(1/\beta = kT\), where \(k\) denotes the Boltzmann constant and \(T\) is the temperature. This characteristic distance is called the Bjerrum length \[\ell_B = \frac{\beta e_0^2}{4\pi\varepsilon\varepsilon_0}\] and is \(\sim 7\,Å\) in water at room temperature. The Bjerrum length in its bare form considers two monovalent ions. With ions of higher valence \(q\), which we are also studying, this length scale is multiplied by a factor of \(q^2\).

Another length scale may be identified by comparing the thermal energy \(kT\) with the potential energy of the counterion in the potential of an infinite charged wall, the so-called Gouy-Chapman length \[\mu = \frac{1}{2\pi q\ell_B \sigma}.\] The Gouy-Chapman length gives a rough measure of the thickness of the counterion layer at a charged wall, as we shall see later. We may employ it to express all lengths as \(\mathbf{\tilde{r}} = \mathbf{r} / \mu\). Then the Hamiltonian 1 may be rewritten in units of thermal energy \begin{equation}\beta H = \sum_i \sum_{j < i} \frac{\Xi}{|\mathbf{\tilde{r}}_j - \mathbf{\tilde{r}}_i|} + \sum_i {\tilde{z}}_j. \label{eq:hamiltionian}\end{equation} The Hamiltonian rewritten in this way depends only on a single parameter \(\Xi\), which we call the coupling parameter and is defined as \[\Xi :=\frac{q^2 \ell_B}{\mu} = 2\pi q^3 \ell_B^2 \sigma\] The coupling parameter rises with the surface charge density, falls inversely with the temperature, and is very strongly dependent on the counterion valence \(q\). Some typical values of the coupling parameter are given in Table 1. The strong-coupling limit \(\Xi \gg 1\) often corresponds to the presence of high-valence counterions, such as spermidine and other multivalent ions, which significantly enhance electrostatic correlations.

| \(\sigma\,[\mathrm{\frac{e_0}{nm^2}}]\) | \(q\) | \(\mu\,[\mathrm{Å}]\) | \(\Xi\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| charged | \(\sim 1\) | 1 | 2.2 | 3.1 |

| membranes | 2 | 1.1 | 24.8 | |

| 3 | 0.7 | 83.7 | ||

| DNA | 0.9 | 1 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| 2 | 1.2 | 22.4 | ||

| 3 | 0.8 | 75.6 | ||

| 4 | 0.6 | 179 | ||

| surfactant | \(\sim 1\) | 3 | 0.7 | 85 |

| micelles | ||||

| polystyrene | \(\sim 0.1\) | 1 | \(\sim 2\) | \(\sim 0.1\) |

| particles |

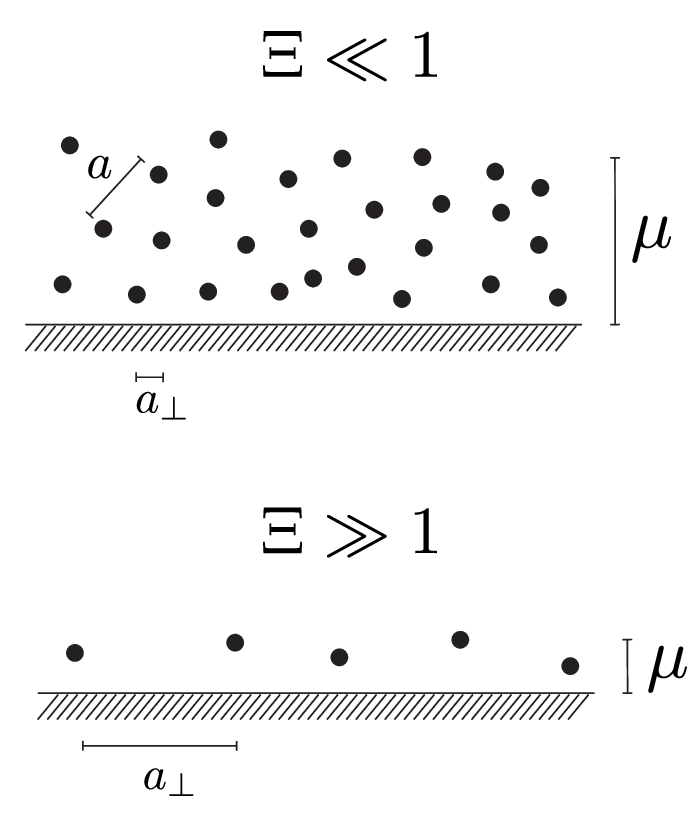

For ions near the macromolecule surface, electroneutrality implies that each valence \(q\) counterion occupies an area of \(q/\sigma\). The diameter of such an area is \(a_\perp = 2\sqrt{q/\pi\sigma}\). In units of Gouy-Chapman length, this radius is determined by the coupling parameter as \[\tilde{a}_\perp :=\left( \frac{a_\perp}{\mu} \right) = \sqrt{8\Xi}.\]

As we have already stated and will confirm later, the counterion layer at the charged macromolecule wall has a thickness of about \(\mu\). Therefore, large values of the coupling parameter, \(\Xi \gg 1\), imply that the lateral distances between individual counterions are large compared to the thickness of the counterion layer. Such a layer is essentially flat and two-dimensional. This regime is depicted in Figure 2 below. At the other extreme, a small value of the coupling parameter \(\Xi \ll 1\) means that the layer is rather diffuse in the \(z\)-direction. Inside the cloud-like layer, its sublayers have no additional correlations in the counterion positions. Instead, correlations are radially symmetric (as seen in Figure 2 above), similar to a three-dimensional fluid.

In the weak coupling regime, the mean-field approximation to the Hamiltonian 2 is applicable. The derivation is beyond the scope of this seminar, but suffice it to say that the many-body Hamiltonian is reformulated as a field theory. When it is then expanded in the limit of \(\Xi \to 0\) [10], it brings us to the Poisson-Boltzmann equation \begin{equation}-\nabla^2 \phi(z) = \frac{q e_0 \rho_0 e^{-\beta q e_0\phi(z)}}{\varepsilon\varepsilon_0}, \label{eq:PB}\end{equation} where \(\phi\) is the electrostatic potential, corresponding to the counterion charge distribution \(\rho\) via the Poisson equation.

In this mean-field description, the counterion configuration is replaced by its thermal average. The correlations between ions are ignored and counterions act independently, obeying the Boltzmann distribution \(\rho(z) = qe_0 \rho_0 e^{-\beta qe_0 \phi}\), dictated by the potential \(\phi(z)\). It is worth noting that the Poisson-Boltzmann equation was historically arrived at from this more heuristic angle, starting with the Poisson equation and having each counterion obey the Boltzmann distribution. The equation is well established and goes back a century, starting with the work of Gouy [3] and Chapman [4].

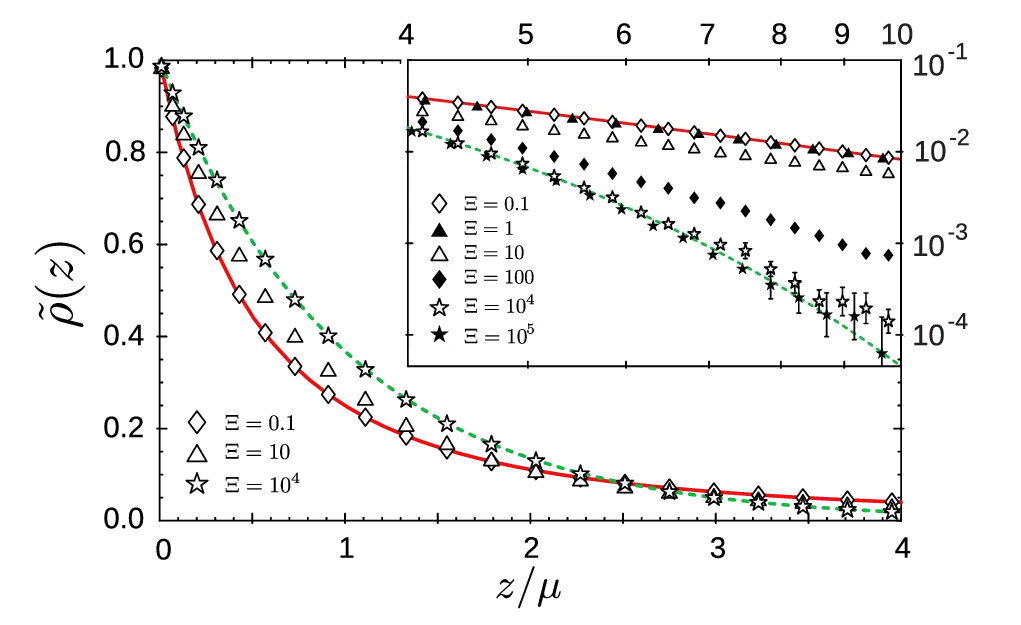

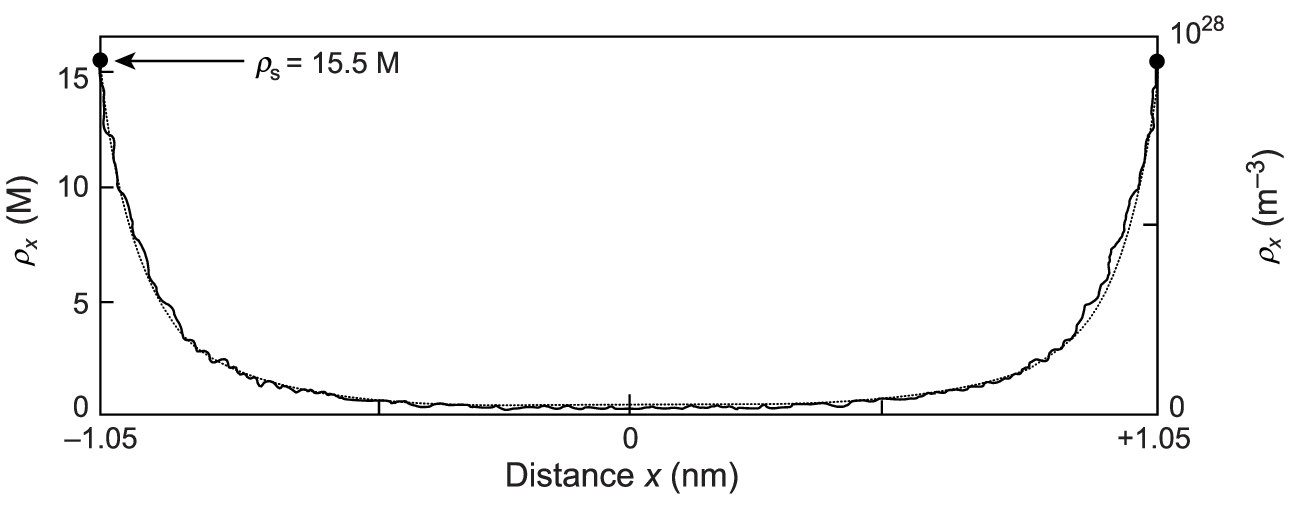

In the single infinite plane geometry, the boundary condition for the Poisson-Boltzmann equation is \(\frac{\mathrm{d}\phi}{\mathrm{d}z}\rvert_{z=0} = -\frac{\sigma e_0}{2\varepsilon\varepsilon_0}\). Introducing \(\phi'(z)\) as a new variable and using this boundary condition, the equation is solved [11] by a potential of the form \begin{equation}\phi(\tilde{z}) = \frac{2kT}{q e_0} \ln(\tilde{z} + 1), \label{eq:potential}\end{equation} where \(\tilde{z} = z/\mu\). We have set this potential’s reference point \(\phi(0) = 0\) at \(z = 0\), with counterion density \(\rho(0) = \rho_0\). From this, a counterion density profile is obtained \begin{equation}\frac{\rho_\mathrm{PB}(z)}{\rho_0} = \frac{1}{\left( \tilde{z} + 1 \right)^2}. \label{eq:algebraic}\end{equation} By inserting the potential 4 back into the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, we get a value of density at the wall surface \begin{equation}\rho_0 = 2\pi \ell_B \sigma^2. \label{eq:contact-value}\end{equation} The algebraic profile 5 for the weak-coupling regime is shown as a solid red line in figure 3.

In the strong-coupling regime, the dominant driver of the dynamics become single-particle interactions between counterions and the charged plane [1]. When \(\Xi \gg 1\), only the second term in the Hamiltonian 2 survives1. We obtain the equilibrium density profile by using the Boltzmann weight of these single-particle counterion-wall interactions \begin{equation}\rho_\mathrm{SC}(z) = \rho_0 e^{-\tilde{z}}. \label{eq:exponential}\end{equation} From integrating this profile (shown in Figure 3 as a green dashed line), the electroneutrality condition gives us the value of \(\rho_0 = 2\pi\ell_B \sigma^2\), exactly matching the Poisson-Boltzmann contact-value 6. This expression for the contact-value density is quite general, holding both for the Poisson-Boltzmann and the strong-coupling approximations.

The weak-coupling and strong-coupling profiles have different functional dependencies, algebraic for the weak-coupling profile 5 and exponential for the strong-coupling profile 7. Despite this, they share the same contact-value density and have the same characteristic length scale \(\mu\), which represents the thickness of the counterion layer.

Two-plate geometry

For now, we have only gained an understanding of how counterion layers behave around a single charged planar macromolecule. If we wish to understand interactions between macromolecules, we must consider two identical planar macromolecules, placed at separation \(D\) from each other.

We will be interested in the effective interaction between two such macromolecules, manifesting as osmotic pressure \(p(D)\) acting on the walls of these two macromolecules. In experimental setups, this pressure is counteracted by the external pressure applied to the system, allowing to control the osmotic pressure and simultaneously observe intermolecular spacings via X-ray diffraction of the periodic structure with period \(D\) (see Figure 1).

In the weak-coupling regime, we will solve the counterion-only Poisson-Boltzmann equation 3, just like we did for the case of a single charged plate. Such Poisson-Boltzmann theory will be shown to always result in repulsive interactions. A need for the strong-coupling regime (and intermediate regimes) will be established, from experimental observations, direct force measurements and Monte-Carlo simulations.

For the strong-coupling regime, a more heuristic argument will suffice to obtain a \(p(D)\) relation with a force, which is attractive by nature for large values of \(D\). This attractive regime is the main takeaway from the WC/SC dichotomy, contradicting the Poisson-Boltzmann theory and the intuitive expectation of repulsive-only Coulomb interactions between like charges.

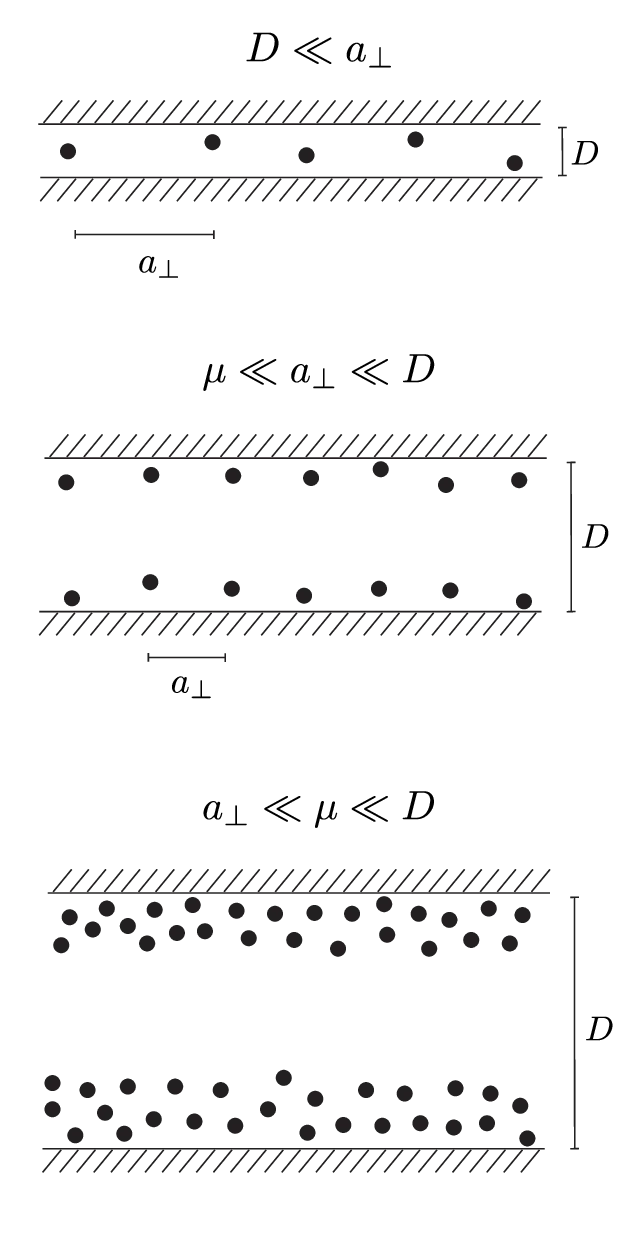

Weak-coupling regime

The weak-coupling regime arises when \(\Xi \ll 1\) and the inter-wall separation \(D\) is large compared with the other two scales \[a_\perp \ll \mu \ll D.\] As illustrated in Figure 4c, counterions form a diffuse layer at each plate2. We have set the coordinate system \(z = 0\) at the midplane. To calculate the pressure acting on one of the walls at \(z = \pm D/2\), we can utilize the contact-value theorem [13], which gives an exact expression for pressure on the planar macromolecule walls \begin{equation}p = kT \rho(z)\rvert_{D/2} - \frac{\sigma^2 e_0^2}{2\varepsilon\varepsilon_0}. \label{eq:contact-value-theorem}\end{equation} The first term is the pressure of counterions on the wall as ideal gas particles. The second term is the electrostatic attraction force, sum of the wall-wall repulsion and wall-counterion attraction. The plate’s field is that of an infinite plate capacitor, i.e. a homogeneous field \(E = \frac{\sigma e_0}{2\varepsilon \varepsilon_0}\). A part of the other plate, associated with area \(A\) and area \(A\sigma e_0\), is repulsed with a force equal to \((A \sigma e_0) \cdot E\). For each unit of charge, present in area \(A\) on one of the two walls, there is two times that amount of charge in the two counterion layers in between the walls. This counterion charge attracts the plate with a force equal to \(2\cdot (A \sigma e_0) \cdot E\).

The attractive counterion-wall force is 2 times as large as the repulsive wall-wall force, their sum being an attractive force equal to \((A\sigma e_0) \cdot E\). Acting on the plate, this manifests as a negative pressure term in equation 8. For practical reasons, we will work with the rescaled pressure, rescaled by the second term in equation 8, \begin{equation}\tilde{p} :=\frac{p}{2\pi \ell_B \sigma^2 kT} = \frac{\rho(z)\rvert_{D/2}}{2\pi\ell_B \sigma^2} - 1. \label{eq:contact-value-rescaled}\end{equation} To get the value of counterion density at the wall \(\rho(z)\rvert_{D/2}\), we must solve the Poisson-Boltzmann equation 3 to obtain a density profile. Without any surface charges at the midplane, the potential has a continuous derivative. By symmetry about the midplane, the electric field \(-\frac{\mathrm{d}\phi}{\mathrm{d}x}\) vanishes at \(z = 0\). Integrating from this midplane boundary condition [14] [11], the potential between the walls is of the form \begin{equation}\phi(\tilde{z}) = \frac{kT}{q e_0} \ln \left( \cos^2 \Lambda \tilde{z} \right) \label{eq:potential-twoplates}\end{equation} As we have assumed in deriving the contact-value theorem 9, the system is composed of two neutral sub-systems (plate plus counterion layer) and the fields emanating from each of the plates are shielded. But near the walls of each plate, the field is that of a bare plate capacitor, acting as a boundary condition \(\frac{\mathrm{d}\phi}{\mathrm{d}z}\rvert_{\pm D/2} = \pm\frac{\sigma e_0}{\varepsilon\varepsilon_0}\). From this, a transcendental equation for the parameter \(\Lambda\) can be written \begin{equation}\frac{1}{\Lambda} = \tan \left( \frac{\Lambda\tilde{D}}{2} \right), \label{eq:transcendental}\end{equation} where \(\tilde{D} = D/\mu\). From the potential, a counterion ion density \(\rho(z) = qe_0 \rho_0 e^{-\beta qe_0 \phi}\) may be obtained, describing the Boltzmann distribution for the solution 10 potential \begin{equation}\rho(\tilde{z}) = \frac{\rho_0}{\cos^2 \Lambda \tilde{z} }. \label{eq:density-profile}\end{equation} This density profile is shown in Figure 5. The constant \(\rho_0 = \rho(0)\) is the reference counterion density at the midplane; its value can be obtained by imposing the electroneutrality condition \[2\sigma = \int_{-D/2}^{D/2} \rho(\tilde{z}) \,\mathrm{d}(\mu \tilde{z}) = \frac{2\mu \rho_0}{\Lambda} \tan \left( \frac{\Lambda\tilde{D}}{2} \right).\] Expressing one \(\Lambda\) from the transcendental equation 11, the midplane density \(\rho_0\) comes out to \begin{equation}\rho_0 = \frac{2\pi \ell_B \sigma^2}{\tan^2 \left( \frac{\Lambda\tilde{D}}{2} \right)} \label{eq:midplane-density}\end{equation}

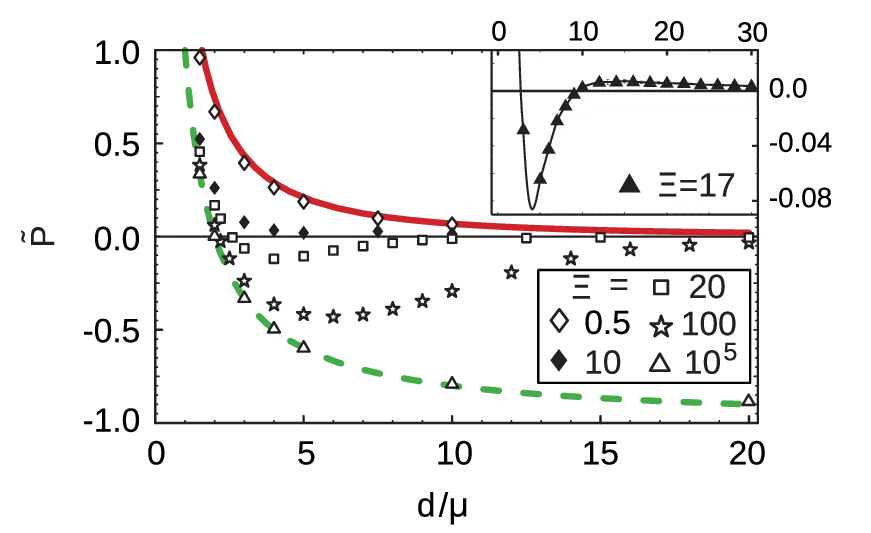

Moving from \(z = 0\) to \(z = \pm D/2\) at the wall, the counterion density follows the profile 12. Substituting in the midplane counterion density, the density at the walls is \[\rho(z)\rvert_{D/2} = \frac{2\pi \ell_B \sigma^2}{\sin^2 \left( \frac{\Lambda \tilde{D}}{2} \right) }\] With the counterion density known, we can evaluate the pressure acting on the wall by the contact-value theorem 9. Using the trigonometric identity \(\sin^{-2}x - 1 = \tan^{-2}x\) and again taking note of the transcendental equation 11 for the parameter \(\Lambda\), the pressure acting on one of the walls is \begin{equation}\tilde{p}_\mathrm{PB}(\tilde{D}) = \Lambda^2. \label{eq:PB-pressure}\end{equation} The obtained pressure \(\tilde{p}_\mathrm{PB}(\tilde{D})\) is shown in 6 as a red line. For large and small values of \(\tilde{D}\), the transcendental equation 11 can be expanded, giving rise to limits \begin{equation}\tilde{p}_\mathrm{PB}(\tilde{D}) = \begin{cases} \pi^2 \tilde{D}^{-2} & \text{for } \tilde{D} \gg 1, \\ 2 \tilde{D}^{-1} - 1/3 & \text{for } \tilde{D} \ll 1. \\ \end{cases} \label{eq:PB-pressure-approx}\end{equation} It is of special note that the pressure 14, shown is always positive, denoting a strictly repulsive interaction. This is a good description for macromolecules in solutions containing monovalent ions. But for polyvalent ions with \(q > 1\), corresponding to much larger values of the coupling parameter (see Table 1), strong counterion correlations arise and the Poisson-Boltzmann mean-field approximation is no longer valid. Experimental data and simulations show that such correlations can result in effective attractive interactions between macromolecules.

Clues pointing to an attractive interaction

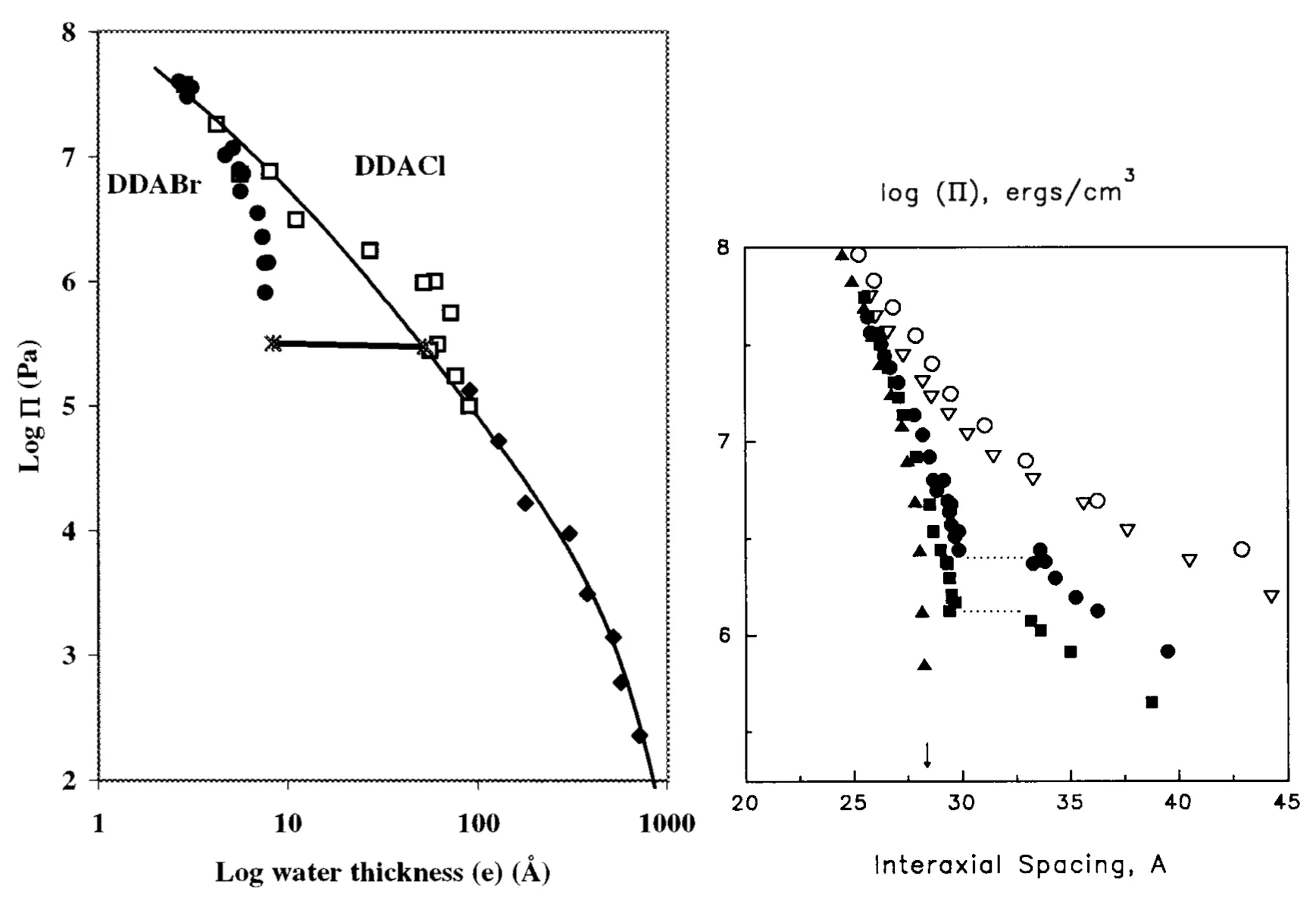

One phenomenon for which the Poisson-Boltzmann approximation breaks down are phase-coexistences observed in experiments with charged lamella [8] [15]. When measured, isotherms of such a system (Figure 7 left) bear resemblance to van der Waals isotherms. From a course on thermodynamics, the reader should be aware that the van der Waals modification of the ideal gas law takes the form of non-monotonic \(p(V)\) isotherms. We are operating at a constant temperature equilibrium, so the stability of equilibrium is determined by the free energy being a convex function of volume \begin{equation}\left( \frac{\partial^2 F}{\partial V^2} \right)_T \ge 0, \label{eq:stability-F}\end{equation} and by \(\mathrm{d}F = -S \mathrm{d}T - p\mathrm{d}V\), this corresponds to a condition for the isotherms to be monotonically non-increasing \[\left( \frac{\partial p}{\partial V} \right)_T \le 0, \text{ or } \left( \frac{\partial p}{\partial D} \right)_T \le 0 \text{ in planar geometry}\] In the case where pressure is not a monotonic function of intermolecular spacing, the free energy is not convex and we observe phase-coexistence. This corresponds to flat phase-transition regions in Figure 7 left. And like the constant-pressure Maxwell construction on the van der Waals isotherm describes a phase transition from liquid water to steam, the flat regions in the \(p(D)\) diagram of charged lamellae (see Figure 7 left) point to an underlying non-monotonic isotherm.

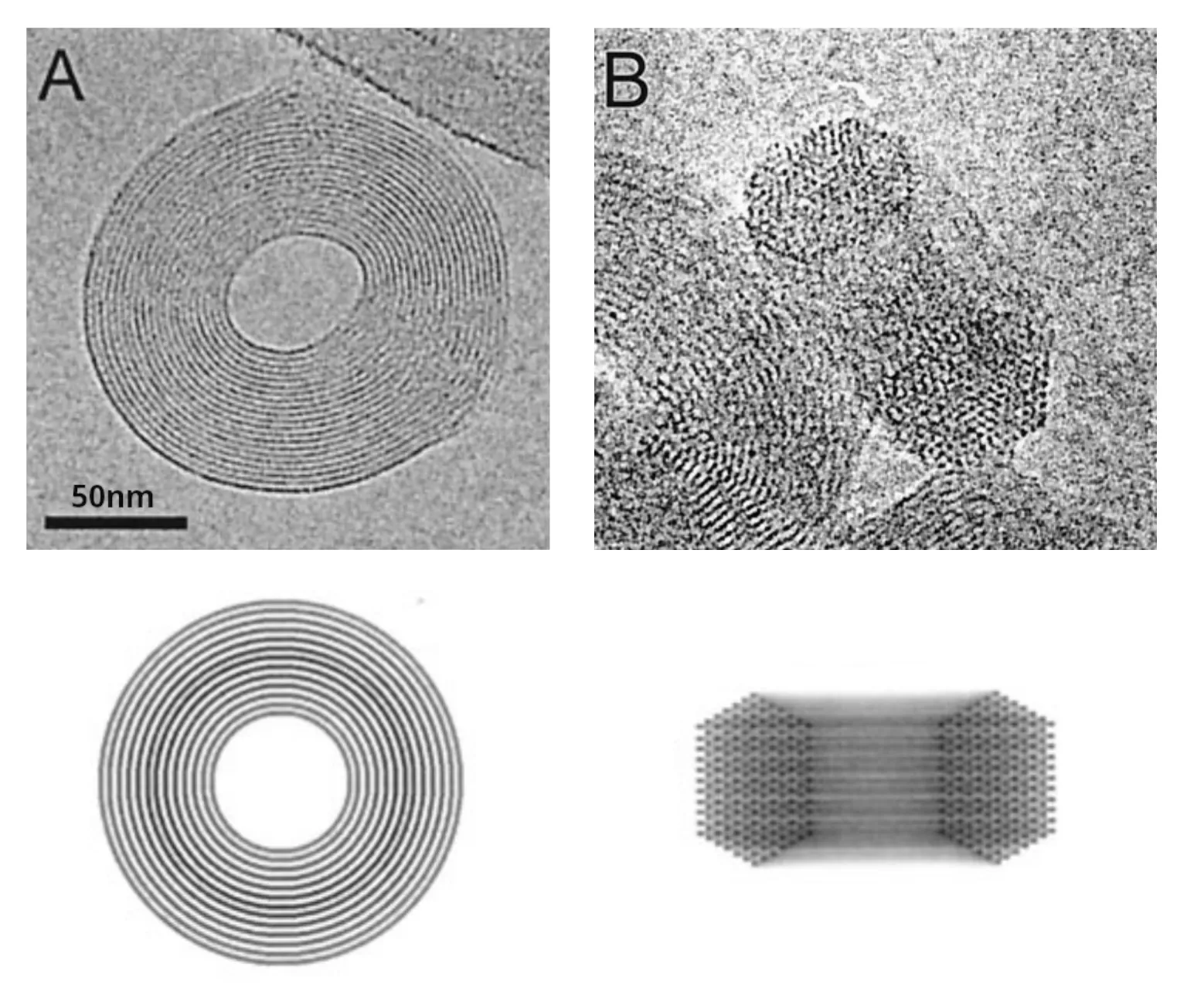

This contradicts the weak-coupling solution and points to the existence of an attractive force regime. We will show this is indeed the case in the strong-coupling regime, where attractive forces between charged macromolecules arise. The flat regions in the \(p(D)\) isotherms are also observed for DNA, as seen in Figure 7 to the right. The corresponding phase transition is DNA condensation. Instead of the naively expected self-repulsion, DNA tightly packs into a torus of \(\sim1\,\mathrm{\mu m}\) in diameter (see Figure 8).

Strong coupling regime

We will now consider the strong-coupling limit of the two-plate system. As already discussed, the strong-coupling \(\Xi \gg 1\) regime gives rise to an almost two-dimensional layer of counterions. In this plane, counterion positions are highly correlated. The system can not anymore be thought about as two neutral subsystems, but as a collection of 2D cells of diameter \(a_\perp \gg D\), each containing a single counterion, sandwiched between the macromolecule walls.

Taking this picture, we will consider the pressure exerted by a single counterion, sandwiched between macromolecule wall sections, each with an area of \(A = q/2\sigma\) to satisfy the electroneutrality condition. Pressure can be calculated from the free energy as \begin{equation}p = -\left( \frac{\partial F}{\partial V} \right)_T = -\left( \frac{\partial \mathcal{F}}{\partial D} \right)_T, \label{eq:F-diff}\end{equation} where \(\mathcal{F} = F/A\) is the free energy per unit area \[\mathcal{F} = \mathcal{E} - T\mathcal{S},\] defined by electrostatic energy per unit area \(\mathcal{E} = E/A\) and entropy per unit area \(\mathcal{S} = S/A\). Pressure on the walls contains both an electrostatic energetic contribution and an entropic contribution. The electrostatic energy \(\mathcal{E}\) is a sum of the interaction terms \(\mathcal{E} = \mathcal{E}_{ww} + \mathcal{E}_{w1} + \mathcal{E}_{w2}\), where \(\mathcal{E}_{ww}\) is the wall-wall interaction, \(\mathcal{E}_{w1}\) and \(\mathcal{E}_{w2}\) are the interactions of the counterion with the left and the right wall. The wall-wall interaction energy may be obtained by considering the plate capacitor potential of the left plate, acting on the corresponding section of the right wall with area \(A\). Expressed in thermal units and per unit area, this wall-wall interaction energy is \begin{equation}\beta \mathcal{E}_{ww} = -2\pi \ell_B \sigma^2 D \label{eq:wall-wall}\end{equation} The energy of wall-counterion interactions is obtained in a similar fashion. We write the potentials of the left plate \(\phi_1\) and the right plate \(\phi_2\). From this, we evaluate the electrostatic energy for the current counterion position \(z\) inside these two potentials \[\begin{aligned} E_{w1} + E_{w2} &= \phi_1 \cdot [qe_0] + \phi_2 \cdot [qe_0] \\ &= \frac{\sigma e_0}{2\varepsilon\varepsilon_0} z \cdot [qe_0] + \frac{\sigma e_0}{2\varepsilon\varepsilon_0} (D-z) \cdot [qe_0] \\ &= 2\pi\ell_B \sigma D. \end{aligned}\] The result was to be expected. The fields of plates with the same charge cancel each other out, resulting in a vanishing electric field in between the plates. The electrostatic energy from wall-counterion interactions is independent of the counterion placement along the \(z\)-axis. Substituting the electroneutrality condition \(q = 2A \sigma\) and expressing in thermal units per unit area, we get \begin{equation}\beta \mathcal{E}_{w1} + \beta \mathcal{E}_{w2} = 4\pi \ell_B \sigma^2 D \label{eq:wall-counterion}\end{equation} Adding up both wall-wall interaction term 18 and the wall-counterion terms 19, we get the total electrostatic energy per unit area \begin{equation}\beta \mathcal{E} = 2\pi \ell_B \sigma^2 D. \label{eq:energy}\end{equation} Besides the energy term, we must additionally consider the entropy term. As the counterion is confined inside the area \(A\) cell, the available number of microstates is proportional only to \(D\). By the Boltzmann entropy formula, the entropy of such a two-dimensionally confined counterion cell is \(S = k \ln D + \text{const}\)3. Adding this entropic term \(\beta T \mathcal{S} = \beta TS / A\) to the electrostatic energy 20, we write the whole free energy per unit area \[\beta \mathcal{F} = 2\pi\ell_B\sigma^2 D - \frac{2\sigma}{q} \ln D\] This expression can now be differentiated as per 17, giving the resulting strong-coupling pressure in rescaled units \begin{equation}\tilde{p}_\mathrm{SC}(\tilde{D}) = -1 + \frac{2}{\tilde{D}}. \label{eq:SC-pressure}\end{equation} The obtained strong-coupling pressure is shown as a green line in 6. While the Poisson-Boltzmann approximation predicted only repulsive interactions, the pressure \(\tilde{p}_\mathrm{SC}(\tilde{D})\) predicts negative pressure at larger separations \(\tilde{D} > 2\). At \(\tilde{D} = 2\), there is a free energy minimum and a bound state. The strong-coupling regime provides an answer as to the mechanism by which an attractive force between similarly charged macromolecules arises.

Applicability of regimes

In deriving the strong-coupling (SC) pressure 21, we have assumed that the counterions are confined inside 2D cells in between the plate walls. It should then be clear that regardless of how high the value of the coupling parameter \(\Xi\) is, this confinement can be broken by simply moving the plates apart (see Figure 4b). For such an arrangement, arguments of section 4.3 are not applicable, as the counterion-wall interaction energy is not independent of the \(z\) position of counterions.

The two-plate geometry contains an additional characteristic scale \(D\), which is just as important in determining the validity of the strong-coupling approximation. Instead of simply considering the coupling constant \(\Xi\), we must consider both \(\Xi\) and this new characteristic scale, plate separation \(D\). The relevant already stated condition for SC to be valid is \(a_\perp \gg D\). This condition can be achieved for virtually any value of \(\Xi\), simply by bringing the plates together, i.e. considering a smaller \(D\). The smaller the value of the coupling constant, the tighter the maximum plate separation gap must be for ions to be effectively confined to 2D cells and the SC approximation to be valid. Simulations show that the counterion layer densities approximately follow that of isolated charged plates [18], but a closed-form theory for this regime is lacking.

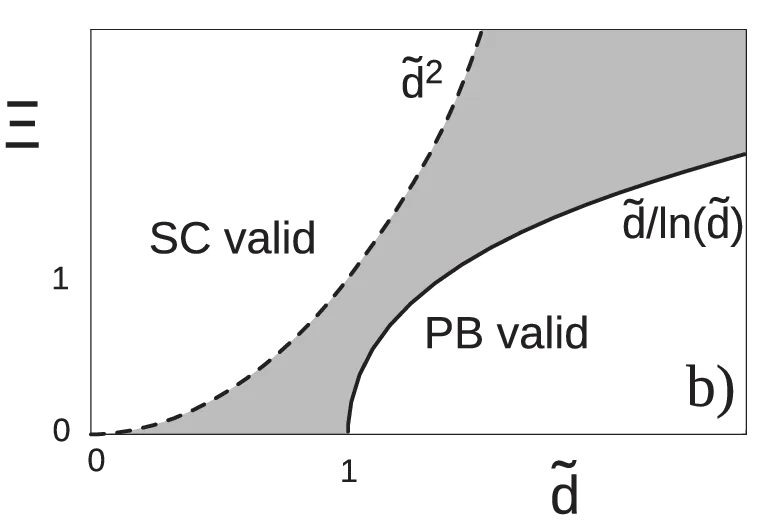

In Ref. [7], the range of validity for the SC regime is estimated by considering next-leading corrections to the SC approximation4. The authors derive that the SC approximation is valid for \begin{equation}\tilde{D} \ll \sqrt{\Xi}, \quad \text{SC valid}, \label{eq:condition-SC}\end{equation} giving a useful criterion for the approximation validity. In a similar fashion, they also give an estimation for the validity range of the Poisson-Boltzmann approximation (see Figure 9), it being valid for \begin{equation}\tilde{D} \gg \Xi / \ln(\Xi), \quad \text{P.B. valid}. \label{eq:condition-PB}\end{equation} In between the SC and the Poisson-Boltzmann regime, there is an intermediate regime not described by either of the SC and the Poisson-Boltzmann approximations \[\sqrt{\Xi} < \tilde{D} < \Xi/\ln(\Xi),\] show in Figure 9 in grey. This intermediate regime evades closed-form treatment [10] [7] and must generally be handled by numerical simulations. In Figure 6, we see some Monte-Carlo simulation results for such intermediate plate separations are shown. The basis for the simulations is a Hamiltonian similar to the single-plate Hamiltonian 2, but with an additional term for the second planar macromolecule. By increasing the coupling parameter, simulations show the strong-coupling profile arising first at small \(\tilde{D}\) (see Figure 6). With an increasing value of \(\Xi\), the SC profile extends to larger and larger separations, again corroborating the validity conditions 22, 23.

Conclusions

To recapitulate, we have explored multiple regimes of the general many-body for the single plate, and more interestingly, for the two-plate geometry. We learned of the importance of the coupling parameter \(\Xi\). The coupling parameter is small for solutions containing monovalent ions. Such a system is well described by the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. In this regime, effective interactions between like-charged macromolecules are strictly repulsive.

The weak-coupling approximation breaks down when polyvalent counterions are brought into the picture. Strong counterion correlations arise, indicated by a large value of the coupling parameter \(\Xi \gg 1\). In the single-plate geometry, the counterion form a quasi-two-dimensional layer near the plate. In two-plate geometry, small-enough plate separations result in only one quasi-two-dimensional layer being sandwiched between the plates. This is the strong-coupling limit (depicted in Figure 4c).

This strong-coupling regime predicts an attractive force at large plate separations \(\tilde{D} > 2\), giving a mechanism for forces behind experimentally observed phase-coexistences in macromolecule solutions (see section 4.2). It must be noted that the strong-coupling regime is rarely entirely physically realized, and mostly serves as a useful concept in understanding correlations between counterions.